Table of Contents

Introduction

此为MIT 6.S081课程和xv6-Books的学习笔记,这一章内容是真的多

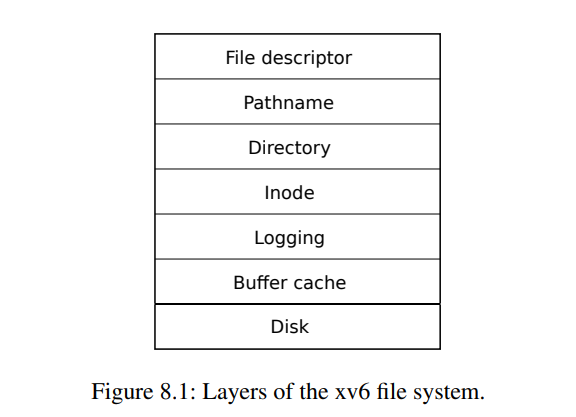

文件系统的目的是组织和存储数据。文件系统通常支持用户和应用程序之间的数据共享,以及持久性,以便在重新启动后数据仍然可用,文件系统是操作系统中除了shell以外最常见的用户接口。如下图所示,xv6文件系统实现分为七层:

- disk layer读取和写入virtio硬盘上的block

- buffer cache layer缓存block并同步其数据,确保某一时间点只有一个内核进程可以修改block中的数据

- logging layer允许更高层在一次事务(transaction)中将更新多个块,并确保在遇到崩溃时原子性的更新这些块

- inode layer是对文件的抽象,每个文件表示为一个inode,其中包含唯一的索引号(i-number)和一些保存文件数据的block

- directory layer将每个目录实现为一种特殊的索引结点,其内容是一系列目录项(directory entries),每个目录项包含一个文件名和索引号

- pathname layer提供了分层路径名,例如/usr/rtm/xv6/fs.c,并通过递归查找来解析文件名

- file descriptor layer使用文件系统接口抽象了许多Unix资源(管道、设备、文件等),简化了程序员的工作

文件系统并不是唯一构建一个存储系统的方式。如果只是在磁盘上存储数据,你可以想出一个完全不同的API。举个例子,数据库也能持久化的存储数据,但是数据库就提供了一个与文件系统完全不一样的API。所以记住这一点很重要:还存在其他的方式能组织存储系统。文件系统通常由操作系统提供,而数据库如果没有直接访问磁盘的权限的话,通常是在文件系统之上实现的(注,早期数据库通常直接基于磁盘构建自己的文件系统,因为早期操作系统自带的文件系统在性能上较差,且写入不是同步的,进而导致数据库的ACID不能保证。不过现代操作系统自带的文件系统已经足够好,所以现代的数据库大部分构建在操作系统自带的文件系统之上)。

首先,最重要的可能就是inode,这是代表一个文件的对象,并且它不依赖于文件名。实际上,inode是通过自身的编号来进行区分的,这里的编号就是个整数。所以文件系统内部通过一个数字,而不是通过文件路径名引用inode。同时,基于之前的讨论,inode必须有一个link count来跟踪指向这个inode的文件名的数量。一个文件(inode)只能在link count为0的时候被删除。实际的过程可能会更加复杂,实际中还有一个openfd count,也就是当前打开了文件的文件描述符计数。一个文件只能在这两个计数器都为0的时候才能被删除。

文件系统中核心的数据结构就是inode和file descriptor。后者主要与用户进程进行交互。

Disk

实际中有两种磁盘最常见,即SSD(固态硬盘)和HDD(机械硬盘),这两类存储虽然有着不同的性能,但是都在合理的成本上提供了大量的存储空间。SSD通常是0.1到1毫秒的访问时间,而HDD通常是在10毫秒量级完成读写一个disk block。

磁盘的一些术语:

- sector通常是磁盘驱动可以读写的最小单元,它过去通常是512字节

- block通常是操作系统或者文件系统视角的数据,它由文件系统定义,通常来说一个block对应了一个或者多个sector。在xv6中它是1024字节(2个sector)

存储设备连接到了电脑总线之上,总线也连接了CPU和内存。文件系统运行在CPU上,数据会以读写block的形式存储在SSD或者HDD。在内部,SSD和HDD工作方式完全不一样,但是对于硬件的抽象屏蔽了这些差异。磁盘驱动通常会使用一些标准的协议,例如PCIE,与磁盘交互。从上向下看磁盘驱动的接口,大部分的磁盘看起来都一样,你可以提供block编号,在驱动中通过写设备的控制寄存器,然后设备就会完成相应的工作。这是从一个文件系统的角度的描述。尽管不同的存储设备有着非常不一样的属性,从驱动的角度来看,你可以以大致相同的方式对它们进行编程。

从文件系统的角度来看磁盘还是很直观的。因为对于磁盘就是读写block或者sector,我们可以将磁盘看作是一个巨大的block的数组,数组从0开始,一直增长到磁盘的最后。

而文件系统的工作就是将所有的数据结构以一种能够在重启之后重新构建文件系统的方式,存放在磁盘上。虽然有不同的方式,但是xv6使用了一种非常简单,但是还挺常见的布局结构:

-

block0被用作boot sector来启动操作系统,通常包含了足够启动操作系统的代码,之后再从文件系统中加载操作系统的更多内容(BIOS 会读取硬盘驱动器上的 boot block,并将控制权转交给 boot block 中的引导程序)

-

block1通常被称为super block,包含有关文件系统的元数据(文件系统大小(以块为单位)、数据块数、索引节点数和日志中的块数),超级块由一个名为mkfs的单独的程序填充,该程序构建初始文件系统,描述了文件系统的布局

-

在xv6中,log block从block2开始,到block32结束。实际上log的大小可能不同,这里在super block中会定义log就是30个block

-

接下来在block32到block45之间,xv6存储了inode block。多个inode会打包存在一个block中,一个inode是64字节(前面说了xv6中一个block是1024字节,也就是16个inode)

-

之后是bitmap block,这是我们构建文件系统的默认方法,它只占据一个block。它记录了数据block是否空闲。

-

之后就全是data block了,数据block存储了文件的具体内容和目录的内容。

通常来说,log blocks、inode blocks和bitmap block被统称为metadata block,它们虽然不存储实际的数据,但是它们存储了能帮助文件系统完成工作的元数据。

// mkfs computes the super block and builds an initial file system. The// super block describes the disk layout:struct superblock { uint magic; // Must be FSMAGIC uint size; // Size of file system image (blocks) uint nblocks; // Number of data blocks uint ninodes; // Number of inodes. uint nlog; // Number of log blocks uint logstart; // Block number of first log block uint inodestart; // Block number of first inode block uint bmapstart; // Block number of first free map block};

#define FSMAGIC 0x10203040//在xv6中,当操作系统加载文件系统时,它会首先读取存储设备的引导块(boot block),然后根据引导//块中的信息找到文件系统的超级块。接着,操作系统会检查超级块的magic字段是否等于FSMAGIC,以确认//文件系统的有效性。如果文件系统的magic字段与FSMAGIC不匹配,操作系统可能会认为文件系统损坏或不//支持该文件系统类型,并采取相应的处理措施,如尝试加载其他文件系统或显示错误信息。//不同的文件系统通常会使用不同的magic numberxv6使用的磁盘是virtio_disk,相关操作代码在virtio_disk.c中,就不细看了(。

Buffer Cache Layer

Buffer cache主要有两个任务:

-

同步对block的访问,以确保block在内存中只有一个副本,并且一次只有一个内核线程使用该副本

-

缓存经常访问的block,以便不需要从磁盘重新读取它们(内存的速度比磁盘快得多的多)

Buffer cache layer提供的接口主要是bread和bwrite:bread获取一个buf(一个可以在内存中读取或修改的block的副本,上锁的);bwrite将修改后的buf写入磁盘上的相应block。Buffer cache layer使用睡眠锁来实现同步机制和控制对每个buf的共享访问,以确保每个buf(也是每个block)每次只被一个线程使用。此外,内核线程在使用完一个buf后必须通过调用brelse释放。

Buffer cache layer中保存磁盘块的buf数量固定,这意味着如果文件系统请求还未存放在buffer cache中的块时,buffer cache会回收最近使用最少的缓冲区(局部性原则,LRU)。

Code

buffer cache部分的代码还是很容易看懂,难点主要在于睡眠锁。首先所有进程都是通过访问bcache这个双向链表来对buf进行读取和修改,其中有个head结点只用于快速索引,不存储相关数据。

每个sector最多只有一个buf。文件系统使用缓冲区上的锁进行同步,buf的睡眠锁保护buf内容的读写,而bcache.lock保护bcache链表的信息。bget在bcache.lock临界区域之外获取buf的睡眠锁是安全的,因为非零b->refcnt防止buf被重新用于不同的磁盘块。如果所有buf都不空闲,表示太多进程同时执行文件系统调用,bget将会panic。PS:xv6这个比较简单,没做太多容错处理,一个更优雅的响应可能是在缓冲区空闲之前休眠,尽管这样可能会出现死锁。一旦bread将buf返回给其调用者,调用者就可以独占使用缓冲区(因为bget返回的是locked的buf),并可以读取或写入数据字节。如果调用者确实修改了buf,则必须在释放buf之前调用bwrite将更改的数据写入磁盘。当调用方使用完buf后,它必须调用brelse来释放缓冲区(brelse是b-release的缩写,起源于Unix,也用于BSD、Linux和Solaris)。brelse释放睡眠锁并将刚使用完的buf移动到bcache.head->next(这样就按使用频率排序了)。

struct buf { int valid; // has data been read from disk?1表示存储有磁盘某一block的数据 int disk; // does disk "own" buf?缓冲区数据是否更新到磁盘block uint dev; uint blockno; struct sleeplock lock; uint refcnt; // 引用次数 struct buf *prev; // LRU cache list struct buf *next; uchar data[BSIZE]; // Block Size 1024B};

struct { struct spinlock lock; struct buf buf[NBUF];

// Linked list of all buffers, through prev/next. // Sorted by how recently the buffer was used. // head.next is most recent, head.prev is least. struct buf head; // 头节点} bcache;

// 比较常规的bcache链表初始化过程voidbinit(void){ struct buf *b;

initlock(&bcache.lock, "bcache");

// Create linked list of buffers bcache.head.prev = &bcache.head; bcache.head.next = &bcache.head; for(b = bcache.buf; b < bcache.buf+NBUF; b++){ b->next = bcache.head.next; b->prev = &bcache.head; initsleeplock(&b->lock, "buffer"); bcache.head.next->prev = b; bcache.head.next = b; }}

// Look through buffer cache for block on device dev.// If not found, allocate a buffer.// In either case, return locked buffer.static struct buf*bget(uint dev, uint blockno){ struct buf *b;

acquire(&bcache.lock);

// Is the block already cached? for(b = bcache.head.next; b != &bcache.head; b = b->next){ if(b->dev == dev && b->blockno == blockno){ b->refcnt++; release(&bcache.lock); acquiresleep(&b->lock); return b; } }

// Not cached. 代码能运行到这已说明缓存中没有这个block,所以下面直接就b->prev // Recycle the least recently used (LRU) unused buffer. for(b = bcache.head.prev; b != &bcache.head; b = b->prev){ // 找当前没有用的buf if(b->refcnt == 0) { b->dev = dev; b->blockno = blockno; b->valid = 0; b->refcnt = 1; release(&bcache.lock); acquiresleep(&b->lock); return b; } } panic("bget: no buffers");}

// Return a locked buf with the contents of the indicated block.struct buf*bread(uint dev, uint blockno){ struct buf *b;

b = bget(dev, blockno); if(!b->valid) { // buf中无有效数据,可见不管咋样内存中也没有某块的buf,都得先读内存中的buf virtio_disk_rw(b, 0); b->valid = 1; } return b;}

// Write b's contents to disk. Must be locked.voidbwrite(struct buf *b){ if(!holdingsleep(&b->lock)) panic("bwrite"); virtio_disk_rw(b, 1);}

// Release a locked buffer.// Move to the head of the most-recently-used list.// 释放的时候更新buffer cache队列,刚释放的就放head->nextvoidbrelse(struct buf *b){ if(!holdingsleep(&b->lock)) panic("brelse");

releasesleep(&b->lock);

acquire(&bcache.lock); b->refcnt--; if (b->refcnt == 0) { // no one is waiting for it.(也就是没有进程需要用这个buf/block了) b->next->prev = b->prev; b->prev->next = b->next; b->next = bcache.head.next; b->prev = &bcache.head; bcache.head.next->prev = b; bcache.head.next = b; }

release(&bcache.lock);}Logging Layer

许多文件系统操作都涉及到对磁盘的多次写入,但部分写操作崩溃后可能会使磁盘上的文件系统处于不一致的状态,因此文件系统设计中最有趣的问题之一是崩溃恢复。例如,假设在文件截断(将文件长度设置为零并释放其内容块)期间发生崩溃。根据磁盘写入的顺序,崩溃可能会留下对标记为空闲的内容块的引用的inode,也可能留下已分配但未引用的内容块。后者相对来说是良性的,但引用已释放块的inode在重新启动后可能会导致严重问题。重新启动后,内核可能会将该块分配给另一个文件,现在我们有两个不同的文件无意中指向同一块。如果xv6支持多个用户,这种情况可能是一个安全问题,因为旧文件的所有者将能够读取和写入新文件中的块,而新文件的所有者是另一个用户。

在文件截断过程中,文件系统通常需要执行以下操作:

- 更新inode:文件系统会更新文件的inode,将其长度设置为零,并释放之前分配的内容块。

- 释放内容块:文件系统会标记之前分配给文件的内容块为free状态,以便可以重新分配给其他文件使用。

当发生崩溃时,可能会出现以下情况:

情况一:崩溃发生在更新inode之前。在这种情况下,文件系统无法将文件的长度设置为零,因此文件仍然保留着之前的长度和内容块。这可能导致文件系统中存在已分配但未被引用的内容块,这些块无法通过正常的文件路径进行访问。

情况二:崩溃发生在释放内容块之前。在这种情况下,文件系统无法将之前分配的内容块标记为自由状态。这可能导致inode仍然引用着被标记为free的内容块,这些内容块可以被其他文件重新分配使用。

xv6通过简单的日志记录形式解决了文件系统操作期间的崩溃问题:xv6系统调用不会直接写入磁盘上的文件系统数据结构。相反,它会在磁盘上的log中放置它希望进行的所有磁盘写入的描述。一旦系统调用记录了它的所有写入操作,它就会向磁盘写入一条特殊的commit记录,表明日志包含一个完整的操作。此时,系统调用将写操作修改到磁盘上的文件系统数据结构。完成这些写入后,系统调用将擦除该日志。

如果系统崩溃并重新启动,则在运行任何进程之前,文件系统代码将按如下方式从崩溃中恢复:如果日志标记为包含完整操作,则恢复代码会通过写操作修改磁盘文件系统中的相应block。如果日志没有标记为包含完整操作,则恢复代码将忽略该日志并擦除。

从上面的描述可以看到xv6通过日志实现对磁盘block同步的原子操作,即要么操作没有发生,要么操作全部完成。

Design

Logging layer由一个header block和一系列更新块的副本(logged block,logged block表示已经记录了操作信息的日志块,而log block仅表示日志块)组成,共分配了30个block。Header block包含一个扇区号数组(每个logged block对应一个扇区号)以及日志块的计数。Header block的计数为零表示日志中没有事务;非零表示日志包含一个完整的已提交事务,并具有指定数量的logged block。只有在事务commit时xv6才向header block写入数据,并在将logged blocks修改到文件系统后将计数设置为零。

考虑到崩溃恢复,磁盘写入序列必须具有原子性。为了允许不同进程并发执行文件系统操作,日志系统可以将多个系统调用的写入累积到一个事务中。因此,单个提交可能涉及多个完整系统调用的写入。为了避免在事务之间拆分系统调用,日志系统仅在没有文件系统调用(对应代码中的outstanding为0)进行时提交。

同时提交多个事务的想法称为组提交(group commit)。组提交减少了磁盘操作的数量,因为多个事务分摊了成本固定的一次提交,组提交还同时为磁盘系统提供更多并发写操作。

xv6保存日志的空间是固定的,也就是说事务中系统调用写入的块总数必须可容纳于该空间。这可能导致两个后果(这部分对应begin op中 else if判断):

- 任何单个系统调用都不允许写入超过日志空间的不同块。这对于大多数系统调用来说都不是问题,但write和unlink可能会写入许多块:一个大文件的write可以写入多个数据块和多个位图块以及一个inode块;unlink大文件可能会写入许多位图块和inode。因此,xv6的write系统调用将大的写入分解为适合日志的多个较小的写入。unlink不会导致此问题,因为实际上xv6文件系统只使用一个位图块。

- 除非确定系统调用的写入将可容纳于日志中剩余的空间,否则日志系统无法允许启动系统调用。

Code

如果只看上面的文字描述其实挺懵的(,细读了log的代码后会好很多。就像上面描述的,xv6中磁盘中log区域分为一个header block和若干logged block,对于logged block的修改是通过header block进行的,由于我们的操作肯定先是在内存中,所以又xv6定义了一个log结构来控制log分区。其次,需要注意的是关于对磁盘的修改都是先修改buf,然后再修改到日志,如果要提交了,再修改到磁盘。

log部分的代码还是有点难度的

系统调用中典型的日志使用如下:

begin_op(); ... bp = bread(...); bp->data[...] = ...; log_write(bp); ... end_op();源代码

struct logheader { int n; // 当前日志中的条目数量 int block[LOGSIZE]; // 对应cache block};

struct log { struct spinlock lock; int start; // start blocknumber int size; int outstanding; // how many FS sys calls are executing. 正在进行的操作数量 int committing; // in commit(), please wait. 是否有其他线程在提交日志 int dev; struct logheader lh;};struct log log; // 内存中的log区域的抽象,包含log的元数据和logheader

// 初始化也就是通过sb和logheader block的相关信息把内存中的log数据结构中的每一项填满// 第一个用户进程运行之前的引导期间由fsinit调用的voidinitlog(int dev, struct superblock *sb){ if (sizeof(struct logheader) >= BSIZE) panic("initlog: too big logheader");

initlock(&log.lock, "log"); log.start = sb->logstart; log.size = sb->nlog; log.dev = dev; recover_from_log();}

static voidrecover_from_log(void){ read_head(); install_trans(); // if committed, copy from log to disk log.lh.n = 0; write_head(); // clear the log}

// Read the log header from disk into the in-memory log header// 读取磁盘中的logheader block到内存中的logstatic voidread_head(void){ struct buf *buf = bread(log.dev, log.start); struct logheader *lh = (struct logheader *) (buf->data); int i; log.lh.n = lh->n; for (i = 0; i < log.lh.n; i++) { log.lh.block[i] = lh->block[i]; } brelse(buf);}

// Copy committed blocks from log to their home location// 将日志中的条目(已经提交了的log block)更新到对应的磁盘上的cache block// PS:晦涩的命名?static voidinstall_trans(void){ int tail;

for (tail = 0; tail < log.lh.n; tail++) { struct buf *lbuf = bread(log.dev, log.start+tail+1); // read log block struct buf *dbuf = bread(log.dev, log.lh.block[tail]); // read dst memmove(dbuf->data, lbuf->data, BSIZE); // copy block to dst bwrite(dbuf); // write dst to disk bunpin(dbuf); brelse(lbuf); brelse(dbuf); }}

// Write in-memory log header to disk.// This is the true point at which the// current transaction commits.// 将内存中的log更新到磁盘中的log header blockstatic voidwrite_head(void){ struct buf *buf = bread(log.dev, log.start); struct logheader *hb = (struct logheader *) (buf->data); int i; hb->n = log.lh.n; for (i = 0; i < log.lh.n; i++) { hb->block[i] = log.lh.block[i]; } bwrite(buf); brelse(buf);}

// called at the start of each FS system call.voidbegin_op(void){ acquire(&log.lock); while(1){ // 有其他线程在提交日志,睡眠等待 if(log.committing){ sleep(&log, &log.lock); } else if(log.lh.n + (log.outstanding+1)*MAXOPBLOCKS > LOGSIZE){ // +1是先加上当前这个操作看是否已经超过了系统预定的LOGSIZE大小 // 保守地假设每个系统调用最多可以写入MAXOPBLOCKS个不同的块 // this op might exhaust log space; wait for commit. sleep(&log, &log.lock); } else { log.outstanding += 1; release(&log.lock); break; } }}

// called at the end of each FS system call.// commits if this was the last outstanding operation.voidend_op(void){ int do_commit = 0; // 是否需要提交日志的标志

acquire(&log.lock); // 这个函数是修改操作的最后才调用的,前面有log_write,因此这里outstanding-1 log.outstanding -= 1; if(log.committing) panic("log.committing"); if(log.outstanding == 0){ do_commit = 1; // 需要提交日志 log.committing = 1; // 一个提交操作正在进行 } else { // begin_op() may be waiting for log space, // and decrementing log.outstanding has decreased // the amount of reserved space. // 这里调用wakeup是因为前面outstanding-1了,前面调用begin_op可能因为LOGSIZE大小导致 // sleep,因此这里wakeup wakeup(&log); } release(&log.lock);

if(do_commit){ // call commit w/o holding locks, since not allowed // to sleep with locks. commit(); acquire(&log.lock); log.committing = 0; wakeup(&log); release(&log.lock); }}

// Copy modified blocks from cache to log.// 将提交的修改从cache(buf)复制到log blockstatic voidwrite_log(void){ int tail;

for (tail = 0; tail < log.lh.n; tail++) { struct buf *to = bread(log.dev, log.start+tail+1); // log block struct buf *from = bread(log.dev, log.lh.block[tail]); // cache block memmove(to->data, from->data, BSIZE); bwrite(to); // write the log brelse(from); brelse(to); }}

// Caller has modified b->data and is done with the buffer.// Record the block number and pin in the cache by increasing refcnt.// commit()/write_log() will do the disk write.//// log_write() replaces bwrite(); a typical use is:// bp = bread(...)// modify bp->data[]// log_write(bp)// brelse(bp)// 这个函数主要作用是更新header中的block数组(记录的是对应的cache block)// 也就是当我们更新一个block时,首先会更新其对应的buf,这个时候我们需要将这个buf添加到log// header中的block数组(如果无)voidlog_write(struct buf *b){ int i;

if (log.lh.n >= LOGSIZE || log.lh.n >= log.size - 1) panic("too big a transaction"); if (log.outstanding < 1) panic("log_write outside of trans");

acquire(&log.lock); for (i = 0; i < log.lh.n; i++) { if (log.lh.block[i] == b->blockno) // log absorbtion break; } log.lh.block[i] = b->blockno; if (i == log.lh.n) { // Add new block to log? // 防止这个block被换出,修改到data block后(install_trans)会调用unpin解除 // bpin和bunpin的代码在缓存部分没有细讲,其实也很简单,无非是增减refcnt,本质还是LRU bpin(b); log.lh.n++; } release(&log.lock);}日志提交的关键代码如下(具体调用的时机为end_op函数):

- 将缓存中被修改的cache block写入对应的log block

- 将内存中log的头部信息更新写入log header block

- log block -> cache block -> data block,完成文件系统的更新

- 更新log header中条目数量为0

- 清空日志,表示事务完成

static voidcommit(){ if (log.lh.n > 0) { write_log(); // Write modified blocks from cache to log write_head(); // Write header to disk -- the real commit install_trans(); // Now install writes to home locations log.lh.n = 0; write_head(); // Erase the transaction from the log }}Block Allocator

文件和目录内容存储在磁盘block中,磁盘block必须从空闲资源池中分配。xv6的块分配器在磁盘上维护一个空闲位图(bitmap),xv6中的bitmap区只有一个block,每一位代表一个块:0表示对应的块是空闲的;1表示它正在使用中。程序mkfs设置对应于引导扇区、超级块、日志块、inode块和位图块的比特位。

块分配器提供两个功能:balloc分配一个新的磁盘块,bfree释放一个块。

位操作给我看麻了,说实话这部分没太看明白

#define BSIZE 1024 // block size// Bitmap bits per block#define BPB (BSIZE*8) // 每个字节8位(*8还想了一会儿,难蚌,都叫“比特位”了!

// Block of free map containing bit for block b#define BBLOCK(b, sb) ((b)/BPB + sb.bmapstart)

// Zero a block.static voidbzero(int dev, int bno){ struct buf *bp;

bp = bread(dev, bno); memset(bp->data, 0, BSIZE); log_write(bp); brelse(bp);}

// Allocate a zeroed disk block.static uintballoc(uint dev){ int b, bi, m; struct buf *bp;

bp = 0; for(b = 0; b < sb.size; b += BPB){ // 遍历所有block bp = bread(dev, BBLOCK(b, sb)); // 得到当前block的位图块号 for(bi = 0; bi < BPB && b + bi < sb.size; bi++){ // bit m = 1 << (bi % 8); if((bp->data[bi/8] & m) == 0){ // Is block free? bp->data[bi/8] |= m; // Mark block in use. log_write(bp); brelse(bp); bzero(dev, b + bi); return b + bi; } } brelse(bp); } panic("balloc: out of blocks");}

// Free a disk block.static voidbfree(int dev, uint b){ struct buf *bp; int bi, m;

bp = bread(dev, BBLOCK(b, sb)); bi = b % BPB; m = 1 << (bi % 8); if((bp->data[bi/8] & m) == 0) panic("freeing free block"); bp->data[bi/8] &= ~m; log_write(bp); brelse(bp);}Inode Layer

接下来我们看一下磁盘上存储的inode究竟是什么?

- 通常来说它有一个type字段,区分文件、目录和特殊文件(设备),type为零表示磁盘inode是空闲的

- nlink字段,也就是link计数器,用来跟踪究竟有多少文件名指向了当前的inode,以便识别何时应释放磁盘上的inode及其数据块

- size字段,表明了文件数据有多少个字节

- 不同文件系统中的表达方式可能不一样,不过在xv6中接下来是一些block的编号,例如编号0,编号1,等等。xv6的inode中总共有12个block编号,这些被称为direct block number,这12个block指向了构成文件的前12个block。举个例子,如果文件只有2个字节,那么只会有一个block编号0,它包含的数字(data block number)是磁盘上文件前2个字节的block的位置。

- 之后还有一个indirect block number,它对应了磁盘上一个block,这个block包含了256(一个block number是4字节(就是地址?),1024/4=256)个block number,这256个block number包含了文件的数据。所以inode中block number 0到block number 11都是direct block number,而block number 12保存的indirect block number指向了另一个block。

基于上面的内容,xv6中文件最大的长度计算可得(256+12) * 1024 = 268KB。这是个很小的文件长度,实际的文件系统,文件最大的长度会大的多得多。实际中可以用类似page table的方式,构建一个双重indirect block number指向一个block,这个block中再包含了256个indirect block number,每一个又指向了包含256个block number的block。这里修改了inode的数据结构,可以使用类似page table的树状结构,也可以按照B树或者其他更复杂的树结构实现。xv6这里极其简单,基本是按照最早的Uinx实现方式来的,不过可以实现更复杂的结构。

假设我们需要读取文件的第8000个字节,那么你该读取哪个block呢?从inode的数据结构中该如何计算呢?

8000 / 1024 = 7 < 12 8000 % 1024 = 832

也就是在第7个block(direct block number)的第832个字节偏移量处就是第8000个字节

Code

inode相关的定义

#define BSIZE 1024 // block size#define NDIRECT 12#define NINDIRECT (BSIZE / sizeof(uint))

// On-disk inode structure// 磁盘上的inode的定义,64字节struct dinode { short type; // File type short major; // Major device number (T_DEVICE only) short minor; // Minor device number (T_DEVICE only) short nlink; // Number of links to inode in file system uint size; // Size of file (bytes) uint addrs[NDIRECT+1]; // Data block addresses};

// in-memory copy of an inode// 内存中对磁盘上inode的副本struct inode { uint dev; // Device number uint inum; // Inode number int ref; // Reference count 引用内存中c指针的数量 指针可以来自文件描述符、 // 当前工作目录和如exec的瞬态内核代码 struct sleeplock lock; // protects everything below here int valid; // inode has been read from disk?

short type; // copy of disk inode short major; short minor; short nlink; uint size;#ifdef SOL_FS#else uint addrs[NDIRECT+1];#endif};

struct { struct spinlock lock; struct inode inode[NINODE];} icache;// 和bcache类似

// Inodes per block.#define IPB (BSIZE / sizeof(struct dinode))

// Block containing inode i#define IBLOCK(i, sb) ((i) / IPB + sb.inodestart)voidiinit(){ int i = 0;

initlock(&icache.lock, "icache"); for(i = 0; i < NINODE; i++) { initsleeplock(&icache.inode[i].lock, "inode"); }}

// Allocate an inode on device dev.// Mark it as allocated by giving it type type.// Returns an unlocked but allocated and referenced inode.// 分配一个空闲的inode在磁盘上,同时最后调用了iget使得这个inode在icache中有标记struct inode*ialloc(uint dev, short type){ int inum; struct buf *bp; struct dinode *dip;

for(inum = 1; inum < sb.ninodes; inum++){ // 找到当前inode所处的inode block bp = bread(dev, IBLOCK(inum, sb)); // 找到具体的inode dip = (struct dinode*)bp->data + inum%IPB; if(dip->type == 0){ // a free inode memset(dip, 0, sizeof(*dip)); dip->type = type; log_write(bp); // mark it allocated on the disk brelse(bp); return iget(dev, inum); } brelse(bp); } panic("ialloc: no inodes");}

// Copy a modified in-memory inode to disk.// Must be called after every change to an ip->xxx field// that lives on disk, since i-node cache is write-through.// Caller must hold ip->lock.// 将内存中修改后的inode信息复制到磁盘中的inodevoidiupdate(struct inode *ip){ struct buf *bp; struct dinode *dip;

bp = bread(ip->dev, IBLOCK(ip->inum, sb)); dip = (struct dinode*)bp->data + ip->inum%IPB; dip->type = ip->type; dip->major = ip->major; dip->minor = ip->minor; dip->nlink = ip->nlink; dip->size = ip->size; memmove(dip->addrs, ip->addrs, sizeof(ip->addrs)); log_write(bp); brelse(bp);}

// Find the inode with number inum on device dev// and return the in-memory copy. Does not lock// the inode and does not read it from disk.// 获取一个内存中的inode(从icache)static struct inode*iget(uint dev, uint inum){ struct inode *ip, *empty;

acquire(&icache.lock);

// Is the inode already cached? empty = 0; // 先遍历icache for(ip = &icache.inode[0]; ip < &icache.inode[NINODE]; ip++){ // 找到有现成的,就把引用计数+1,然后返回inode if(ip->ref > 0 && ip->dev == dev && ip->inum == inum){ ip->ref++; release(&icache.lock); return ip; } // 如果没有现成的,但是某一个icache中的inode的引用为0,把这个空的(第一个)赋给empty if(empty == 0 && ip->ref == 0) // Remember empty slot. empty = ip; }

// Recycle an inode cache entry. // 返回刚刚标记的那个inode if(empty == 0) panic("iget: no inodes");

ip = empty; ip->dev = dev; ip->inum = inum; ip->ref = 1; ip->valid = 0; release(&icache.lock);

return ip;}

// Increment reference count for ip.// Returns ip to enable ip = idup(ip1) idiom.struct inode*idup(struct inode *ip){ acquire(&icache.lock); ip->ref++; release(&icache.lock); return ip;}

// Lock the given inode.// Reads the inode from disk if necessary.// 上睡眠锁(读取/写入inode元数据或内容前,必须得或睡眠锁)voidilock(struct inode *ip){ struct buf *bp; struct dinode *dip;

if(ip == 0 || ip->ref < 1) panic("ilock");

acquiresleep(&ip->lock);

if(ip->valid == 0){ bp = bread(ip->dev, IBLOCK(ip->inum, sb)); dip = (struct dinode*)bp->data + ip->inum%IPB; ip->type = dip->type; ip->major = dip->major; ip->minor = dip->minor; ip->nlink = dip->nlink; ip->size = dip->size; memmove(ip->addrs, dip->addrs, sizeof(ip->addrs)); brelse(bp); ip->valid = 1; if(ip->type == 0) panic("ilock: no type"); }}

// Unlock the given inode.// 解锁voidiunlock(struct inode *ip){ if(ip == 0 || !holdingsleep(&ip->lock) || ip->ref < 1) panic("iunlock");

releasesleep(&ip->lock);}

// Drop a reference to an in-memory inode.// If that was the last reference, the inode cache entry can// be recycled.// If that was the last reference and the inode has no links// to it, free the inode (and its content) on disk.// All calls to iput() must be inside a transaction in// case it has to free the inode.// 减少指向inode的指针计数,如果ref是1即最后一次引用,则清除数据,注意这里频繁的获取和释放// icache的锁,很有意思voidiput(struct inode *ip){ acquire(&icache.lock);

if(ip->ref == 1 && ip->valid && ip->nlink == 0){ // inode has no links and no other references: truncate and free.

// ip->ref == 1 means no other process can have ip locked, 1表示只有调用iput的 // 线程指向这个inode // so this acquiresleep() won't block (or deadlock). acquiresleep(&ip->lock);

release(&icache.lock);

itrunc(ip); ip->type = 0; // 未分配 iupdate(ip); ip->valid = 0;

releasesleep(&ip->lock);

acquire(&icache.lock); }

ip->ref--; release(&icache.lock);}

// Truncate inode (discard contents).// Caller must hold ip->lock.// 清除inode上的block的数据,即将文件截断为0voiditrunc(struct inode *ip){ int i, j; struct buf *bp; uint *a;

for(i = 0; i < NDIRECT; i++){ if(ip->addrs[i]){ bfree(ip->dev, ip->addrs[i]); ip->addrs[i] = 0; } }

if(ip->addrs[NDIRECT]){ bp = bread(ip->dev, ip->addrs[NDIRECT]); a = (uint*)bp->data; for(j = 0; j < NINDIRECT; j++){ if(a[j]) bfree(ip->dev, a[j]); } brelse(bp); bfree(ip->dev, ip->addrs[NDIRECT]); ip->addrs[NDIRECT] = 0; }

ip->size = 0; iupdate(ip);}

// Common idiom: unlock, then put.voidiunlockput(struct inode *ip){ iunlock(ip); iput(ip);}

// Inode content//// The content (data) associated with each inode is stored// in blocks on the disk. The first NDIRECT block numbers// are listed in ip->addrs[]. The next NINDIRECT blocks are// listed in block ip->addrs[NDIRECT].

// Return the disk block address of the nth block in inode ip.// If there is no such block, bmap allocates one.// 返回索引结点ip的第bn个数据块的磁盘块号,如果ip还没有这样的块,bmap会分配一个,涉及到前面// Block allocator的代码static uintbmap(struct inode *ip, uint bn){ uint addr, *a; struct buf *bp;

if(bn < NDIRECT){ if((addr = ip->addrs[bn]) == 0) ip->addrs[bn] = addr = balloc(ip->dev); return addr; } bn -= NDIRECT;

if(bn < NINDIRECT){ // Load indirect block, allocating if necessary. if((addr = ip->addrs[NDIRECT]) == 0) ip->addrs[NDIRECT] = addr = balloc(ip->dev); bp = bread(ip->dev, addr); a = (uint*)bp->data; if((addr = a[bn]) == 0){ a[bn] = addr = balloc(ip->dev); log_write(bp); } brelse(bp); return addr; }

panic("bmap: out of range");}

// Copy stat information from inode.// Caller must hold ip->lock.// 通过stat来获取inode的元数据,不直接读取inode数据voidstati(struct inode *ip, struct stat *st){ st->dev = ip->dev; st->ino = ip->inum; st->type = ip->type; st->nlink = ip->nlink; st->size = ip->size;}

// Read data from inode.// Caller must hold ip->lock.// If user_dst==1, then dst is a user virtual address;// otherwise, dst is a kernel address.intreadi(struct inode *ip, int user_dst, uint64 dst, uint off, uint n){ uint tot, m; struct buf *bp; // 检查读入的偏移量是否超出了文件大小的范围 if(off > ip->size || off + n < off) return 0; if(off + n > ip->size) n = ip->size - off;

for(tot=0; tot<n; tot+=m, off+=m, dst+=m){ bp = bread(ip->dev, bmap(ip, off/BSIZE)); m = min(n - tot, BSIZE - off%BSIZE); if(either_copyout(user_dst, dst, bp->data + (off % BSIZE), m) == -1) { brelse(bp); break; } brelse(bp); } return tot;}

// Write data to inode.// Caller must hold ip->lock.// If user_src==1, then src is a user virtual address;// otherwise, src is a kernel address.intwritei(struct inode *ip, int user_src, uint64 src, uint off, uint n){ uint tot, m; struct buf *bp; // 检查写入的偏移量是否超出了文件大小的范围 if(off > ip->size || off + n < off) return -1; // 检查写入的数据长度是否超过文件系统支持的最大文件大小 if(off + n > MAXFILE*BSIZE) return -1;

// 循环写入数据,直到写入的数据长度等于n for(tot=0; tot<n; tot+=m, off+=m, src+=m){ bp = bread(ip->dev, bmap(ip, off/BSIZE)); m = min(n - tot, BSIZE - off%BSIZE); if(either_copyin(bp->data + (off % BSIZE), user_src, src, m) == -1) { brelse(bp); break; } log_write(bp); brelse(bp); }

if(n > 0){ if(off > ip->size) ip->size = off; // write the i-node back to disk even if the size didn't change // because the loop above might have called bmap() and added a new // block to ip->addrs[]. iupdate(ip); }

return n;}Directory Layer

在xv6中,文件目录结构极其简单,目录的内部实现很像文件,其inode的type为T_DIR,其数据是一系列目录条目(directory entries),每个条目(entry)都是一个struct dirent,每一条entry大小为16个字节:

- 前2个字节包含了目录中文件或者子目录的inode编号

- 接下来的14个字节包含了文件或者子目录名

// Directory is a file containing a sequence of dirent structures.#define DIRSIZ 14

struct dirent { ushort inum; char name[DIRSIZ];};对于实现路径名查找,上述信息就足够了。假设我们要查找路径名“/y/x”,我们该怎么做呢?

从路径名我们知道,应该从root inode开始查找。通常root inode会有固定的inode编号,在xv6中,这个编号是1。inode从block 32开始(block区的第一个block),如果是inode1,那么必然在block 32中的64到128字节的位置(一个inode64字节,最开始有个header inode)。

对于路径名查找程序,接下来就是扫描root inode包含的所有block,以找到“y”,也就是读取所有的direct block number和indirect block number。结果可能是找到了,也可能是没有找到。如果找到了,那么目录y也会有一个inode编号,假设是251。我们可以继续从inode 251查找,先读取inode 251的内容,之后再扫描inode所有对应的block,找到“x”并得到文件x对应的inode编号,最后将其作为路径名查找的结果返回。

xv6对于目录和文件的查找设计的很简单,即通过线性扫描实现。实际的文件系统会使用更复杂的数据结构来使得查找更快。

关于xv6中关于inodes的具体过程,直接看Frans的讲解,比较清晰。

Code

// 常规的字符串比较,比较两个目录的名字(0表示一致,否则返回第一个不相等的字符差值)intnamecmp(const char *s, const char *t){ return strncmp(s, t, DIRSIZ);}

// Look for a directory entry in a directory.// If found, set *poff to byte offset of entry.// 在目录中搜索具有给定名称的条目。如果找到一个,它将返回一个指向相应inode的指针,并将*poff设// 置为目录中条目的字节偏移量,以满足调用方希望对其进行编辑的情形struct inode*dirlookup(struct inode *dp, char *name, uint *poff){ uint off, inum; struct dirent de;

if(dp->type != T_DIR) panic("dirlookup not DIR");

for(off = 0; off < dp->size; off += sizeof(de)){ if(readi(dp, 0, (uint64)&de, off, sizeof(de)) != sizeof(de)) panic("dirlookup read"); if(de.inum == 0) continue; if(namecmp(name, de.name) == 0){ // entry matches path element if(poff) *poff = off; inum = de.inum; return iget(dp->dev, inum); } }

return 0;}

// Write a new directory entry (name, inum) into the directory dp.// 将给定名称和inode编号的新目录条目写入目录dp。intdirlink(struct inode *dp, char *name, uint inum){ int off; struct dirent de; struct inode *ip;

// Check that name is not present. if((ip = dirlookup(dp, name, 0)) != 0){ iput(ip); return -1; }

// Look for an empty dirent. for(off = 0; off < dp->size; off += sizeof(de)){ if(readi(dp, 0, (uint64)&de, off, sizeof(de)) != sizeof(de)) panic("dirlink read"); if(de.inum == 0) break; }

strncpy(de.name, name, DIRSIZ); de.inum = inum; if(writei(dp, 0, (uint64)&de, off, sizeof(de)) != sizeof(de)) panic("dirlink");

return 0;}Path Name Layer

这一层主要是涉及对目录的操作(dirlookup),主要包括下面几个函数。

// Examples:// skipelem("a/bb/c", name) = "bb/c", setting name = "a"// skipelem("///a//bb", name) = "bb", setting name = "a"// skipelem("a", name) = "", setting name = "a"// skipelem("", name) = skipelem("////", name) = 0//// 从路径字符串中提取路径中的第一个元素(目录或文件名,赋值给name),并返回剩余的路径static char*skipelem(char *path, char *name){ char *s; int len; // 跳过开头的/ while(*path == '/') path++; // 如果直接是'\0',则表示路径结束,只有斜杠字符 if(*path == 0) return 0; s = path; // 找到下一个斜杆字符或者结束字符 while(*path != '/' && *path != 0) path++; len = path - s; if(len >= DIRSIZ) memmove(name, s, DIRSIZ); else { memmove(name, s, len); name[len] = 0; } // 跳过/ while(*path == '/') path++; return path;}

// Look up and return the inode for a path name.// If parent != 0, return the inode for the parent and copy the final// path element into name, which must have room for DIRSIZ bytes.// Must be called inside a transaction since it calls iput().// 查找并返回给定路径名的 inode,如果 nameiparent 参数为非零值,则返回父目录的 inode,并将最后的路径元素(目录或文件名)复制到 name 中static struct inode*namex(char *path, int nameiparent, char *name){ struct inode *ip, *next; // 下面这个if-else就是绝对路径和相对路径的区别了 // 根目录的处理,绝对路径 if(*path == '/') ip = iget(ROOTDEV, ROOTINO); else // 当前线程使用文件,相对路径 ip = idup(myproc()->cwd); // 遍历path while((path = skipelem(path, name)) != 0){ ilock(ip); // 看看当前线程使用的文件是不是目录,不是就解锁然后直接返回0 if(ip->type != T_DIR){ iunlockput(ip); return 0; } // 如果需要返回父目录inode,并且当前已是最后一级目录,则停止在当前目录层级 if(nameiparent && *path == '\0'){ // Stop one level early. iunlock(ip); return ip; } // 在当前目录中查找下一个元素的inode,为空的话就解锁直接返回0 if((next = dirlookup(ip, name, 0)) == 0){ iunlockput(ip); return 0; } iunlockput(ip); ip = next; } // path遍历完毕 if(nameiparent){ iput(ip); return 0; } return ip;}

struct inode*namei(char *path){ char name[DIRSIZ]; return namex(path, 0, name);}

struct inode*nameiparent(char *path, char *name){ return namex(path, 1, name);}File Descriptor Layer

“Unix万物皆文件”是Unix操作系统的一个重要理念,它表达了Unix系统中对各种设备和资源的抽象方式。在Unix中,几乎所有的东西都被视为文件。这包括普通文件、目录、设备、网络套接字、管道以及其他类型的资源。通过将这些不同类型的实体都抽象为文件,Unix提供了一种统一的接口和操作方式。这种抽象的好处在于,用户和程序可以使用相同的方式来访问和处理不同类型的实体。无论是读取文件、写入文件、创建目录,还是与设备进行通信,都可以使用类似的文件操作系统调用(如打开、读取、写入、关闭)来完成。这种一致性使得Unix系统更加简洁、灵活和易于使用。文件描述符层则是实现这种一致性的层。

正如我们在第1章中看到的,xv6为每个进程提供了自己的打开文件列表或文件描述符。每个打开的文件都由一个struct file表示,它是inode或管道的封装,加上一个I/O偏移量。每次调用open都会创建一个新的打开文件(一个新的struct file):如果多个进程独立地打开同一个文件,那么不同的实例将具有不同的I/O偏移量。另一方面,单个打开的文件(同一个struct file)可以多次出现在一个进程的文件表中,也可以出现在多个进程的文件表中。如果一个进程使用open打开文件,然后使用dup创建别名,或使用fork与子进程共享,就会发生这种情况。引用计数跟踪对特定打开文件的引用数。可以打开文件进行读取或写入,也可以同时进行读取和写入。readable和writable字段可跟踪此操作。

struct file {#ifdef LAB_NET enum { FD_NONE, FD_PIPE, FD_INODE, FD_DEVICE, FD_SOCK } type;#else enum { FD_NONE, FD_PIPE, FD_INODE, FD_DEVICE } type;#endif int ref; // reference count char readable; char writable; struct pipe *pipe; // FD_PIPE struct inode *ip; // FD_INODE and FD_DEVICE#ifdef LAB_NET struct sock *sock; // FD_SOCK#endif uint off; // FD_INODE short major; // FD_DEVICE};系统中所有打开的文件都保存在全局文件表ftable中。文件表具有分配文件(filealloc)、创建重复引用(filedup)、释放引用(fileclose)以及读取和写入数据(fileread和filewrite)的函数。

struct { struct spinlock lock; struct file file[NFILE]; // xv6规定打开的文件数量为100} ftable;Code

voidfileinit(void){ initlock(&ftable.lock, "ftable");}

// Allocate a file structure.// 在ftable中为打开的file分配一个filestruct file*filealloc(void){ struct file *f;

acquire(&ftable.lock); for(f = ftable.file; f < ftable.file + NFILE; f++){ if(f->ref == 0){ f->ref = 1; release(&ftable.lock); return f; } } release(&ftable.lock); return 0;}

// Increment ref count for file f.// 创建重复引用(需要f->ref>=1)struct file*filedup(struct file *f){ acquire(&ftable.lock); if(f->ref < 1) panic("filedup"); f->ref++; release(&ftable.lock); return f;}

// Close file f. (Decrement ref count, close when reaches 0.)voidfileclose(struct file *f){ struct file ff;

acquire(&ftable.lock); if(f->ref < 1) panic("fileclose"); // 当前还有其他线程在使用这个file,不允许关闭 if(--f->ref > 0){ release(&ftable.lock); return; } // 使用临时变量来关闭file(因为此时我们还持有ftable的锁) ff = *f; // 设置为关闭 f->ref = 0; f->type = FD_NONE; release(&ftable.lock);

if(ff.type == FD_PIPE){ pipeclose(ff.pipe, ff.writable); } else if(ff.type == FD_INODE || ff.type == FD_DEVICE){ begin_op(); iput(ff.ip); end_op(); }}

// Get metadata about file f.// addr is a user virtual address, pointing to a struct stat.// 获取file(只允许inode)的元数据(通过stati),复制到addr(虚拟地址)中intfilestat(struct file *f, uint64 addr){ struct proc *p = myproc(); struct stat st;

if(f->type == FD_INODE || f->type == FD_DEVICE){ ilock(f->ip); stati(f->ip, &st); iunlock(f->ip); if(copyout(p->pagetable, addr, (char *)&st, sizeof(st)) < 0) return -1; return 0; } return -1;}

// Read from file f.// addr is a user virtual address.intfileread(struct file *f, uint64 addr, int n){ int r = 0;

if(f->readable == 0) return -1;

if(f->type == FD_PIPE){ r = piperead(f->pipe, addr, n); } else if(f->type == FD_DEVICE){ if(f->major < 0 || f->major >= NDEV || !devsw[f->major].read) return -1; r = devsw[f->major].read(1, addr, n); } else if(f->type == FD_INODE){ ilock(f->ip); if((r = readi(f->ip, 1, addr, f->off, n)) > 0) f->off += r; iunlock(f->ip); } else { panic("fileread"); }

return r;}

// Write to file f.// addr is a user virtual address.intfilewrite(struct file *f, uint64 addr, int n){ int r, ret = 0;

if(f->writable == 0) return -1;

if(f->type == FD_PIPE){ ret = pipewrite(f->pipe, addr, n); } else if(f->type == FD_DEVICE){ if(f->major < 0 || f->major >= NDEV || !devsw[f->major].write) return -1; ret = devsw[f->major].write(1, addr, n); } else if(f->type == FD_INODE){ // write a few blocks at a time to avoid exceeding // the maximum log transaction size, including // i-node, indirect block, allocation blocks, // and 2 blocks of slop for non-aligned writes. // this really belongs lower down, since writei() // might be writing a device like the console. int max = ((MAXOPBLOCKS-1-1-2) / 2) * BSIZE; int i = 0; while(i < n){ int n1 = n - i; if(n1 > max) n1 = max;

begin_op(); ilock(f->ip); if ((r = writei(f->ip, 1, addr + i, f->off, n1)) > 0) f->off += r; iunlock(f->ip); end_op();

if(r < 0) break; if(r != n1) panic("short filewrite"); i += r; } ret = (i == n ? n : -1); } else { panic("filewrite"); }

return ret;}System Calls

通过使用前面底层提供的函数,大多数系统调用的实现都很简单,xv6中的系统调用代码位于sysfile.c中。

Real World

实际操作系统中的buffer cache比xv6复杂得多,但功能一致:缓存和同步对磁盘的访问。xv6的buffer cache使用简单的LRU替换策略;有许多更复杂的策略可以实现,每种策略都适用于某些工作场景,而不适用于其他某些工作场景。更高效的LRU缓存将消除链表,而改为使用哈希表进行查找,并使用堆进行LRU替换。现代buffer cache通常与虚拟内存系统集成,以支持内存映射文件。

xv6的日志系统效率低下,提交不能与文件系统调用同时发生。系统记录整个块,即使一个块中只有几个字节被更改。它执行同步日志写入,每次写入一个块,每个块可能需要整个磁盘旋转时间。真正的日志系统解决了所有这些问题。

日志记录不是提供崩溃恢复的唯一方法。早期的文件系统在重新启动期间使用了一个清道夫程序(例如,UNIX的fsck程序)来检查每个文件和目录以及块和索引节点空闲列表,查找并解决不一致的问题。清理大型文件系统可能需要数小时的时间,而且在某些情况下,无法以导致原始系统调用原子化的方式解决不一致问题。从日志中恢复要快得多,并且在崩溃时会导致系统调用原子化。

Xv6使用的索引节点和目录的基础磁盘布局与早期UNIX相同;这一方案多年来经久不衰。BSD的UFS/FFS和Linux的ext2/ext3使用基本相同的数据结构。文件系统布局中最低效的部分是目录,它要求在每次查找期间对所有磁盘块进行线性扫描。当目录只有几个磁盘块时,这是合理的,但对于包含许多文件的目录来说,开销巨大。Microsoft Windows的NTFS、Mac OS X的HFS和Solaris的ZFS(仅举几例)将目录实现为磁盘上块的平衡树。这很复杂,但可以保证目录查找在对数时间内完成(即时间复杂度为O(logn))。

Xv6对于磁盘故障的解决很初级:如果磁盘操作失败,Xv6就会调用panic。这是否合理取决于硬件:如果操作系统位于使用冗余屏蔽磁盘故障的特殊硬件之上,那么操作系统可能很少看到故障,因此panic是可以的。另一方面,使用普通磁盘的操作系统应该预料到会出现故障,并能更优雅地处理它们,这样一个文件中的块丢失不会影响文件系统其余部分的使用。

Xv6要求文件系统安装在单个磁盘设备上,且大小不变。随着大型数据库和多媒体文件对存储的要求越来越高,操作系统正在开发各种方法来消除“每个文件系统一个磁盘”的瓶颈。基本方法是将多个物理磁盘组合成一个逻辑磁盘。RAID等硬件解决方案仍然是最流行的,但当前的趋势是在软件中尽可能多地实现这种逻辑。这些软件实现通常允许通过动态添加或删除磁盘来扩展或缩小逻辑设备等丰富功能。当然,一个能够动态增长或收缩的存储层需要一个能够做到这一点的文件系统:xv6使用的固定大小的inode块阵列在这样的环境中无法正常工作。将磁盘管理与文件系统分离可能是最干净的设计,但两者之间复杂的接口导致了一些系统(如Sun的ZFS)将它们结合起来。

Xv6的文件系统缺少现代文件系统的许多其他功能;例如,它缺乏对快照和增量备份的支持。

现代Unix系统允许使用与磁盘存储相同的系统调用访问多种资源:命名管道、网络连接、远程访问的网络文件系统以及监视和控制接口,如/proc(注:Linux 内核提供了一种通过/proc文件系统,在运行时访问内核内部数据结构、改变内核设置的机制。proc文件系统是一个伪文件系统,它只存在内存当中,而不占用外存空间。它以文件系统的方式为访问系统内核数据的操作提供接口。)。不同于xv6中fileread和filewrite的if语句,这些系统通常为每个打开的文件提供一个函数指针表,每个操作一个,并通过函数指针来援引inode的调用实现。网络文件系统和用户级文件系统提供了将这些调用转换为网络RPC并在返回之前等待响应的函数。